On June 30th, a memorial service was held at the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, CO for one of the Air Force's greatest combat leaders.

Robin Olds was one of many successful Army Air Force, and later USAF, pilots in World War Two and peacetime. He became unique by returning to combat in the Vietnam War, becoming a leading MiG-killer while inspiring the fighter wing he commanded to new heights. Olds is most famous for leading Operation Bolo, in which missile-armed F-4 Phantoms masqueraded as F-105 Thunderchief bombers to lure North Vietnamese MiGs into battle on the USAF's terms.

Born in 1922, Olds was raised among warriors and wanted to follow their path. His father was an aide to General Billy Mitchell and a fellow believer in the potential of aerial bombing. When war broke out in Europe in 1939, the younger Olds tried to get involved by joining the Royal Canadian Air Force. Rather than give him permission to fight with an ally, his father insisted that Olds go to West Point instead.

There his many accomplishments began. Olds was named an All-American right tackle while playing for the Army's football team. After earning his wings, he joined the 479th Fighter Group in the D-Day month of June 1944. He scored thirteen aerial victories in P-38s and P-51s, destroyed 11.5 enemy aircraft on the ground, and rose to commander of the 434th Fighter Squadron. After the war, he flew P-80 Shooting Stars with the Air Force's first all-jet demonstration team at March Field, California. He married a movie star, Ella Raines. On an exchange posting with the Royal Air Force he commanded a squadron of Gloster Meteor fighters, becoming the first foreigner to command a regular RAF unit. Between staff tours, he commanded an F-86 Sabre squadron in West Germany and an F-101 Voodoo wing in England.

But as his career progressed, Olds lost favour with his superiors for not fitting their vision of a commander. He was supposed to hold the official Air Force position that air warfare in the future would involve missiles and nuclear weapons, not argue that cannons and conventional bombs were still necessary. He was supposed to network with other officers to further his career, but he chose instead to focus on the men under his command. When assigned to superiors who had not proven themselves in combat, he showed them no respect. Although a Major at the end of WWII, 20 years later he had only risen to Colonel.

His career might have been heading for a dead-end if Air Force senior leadership had not recognized that he was just the man to give spark to the USAF's unsuccessful air combat forces in Southeast Asia. When he left for Vietnam he was infamous. When he returned he was a legend.

A great leader was sorely needed in the theatre. USAF operations over North Vietnam were hampered by political control of targeting and tactics. As Olds had foretold, the Air Force's missile-armed fighters, designed to shoot down docile targets at long range, were ill-equipped to counter hit-and-run attacks by small, nimble North Vietnamese MiGs. When the USAF jets were able to fire their missiles, poor reliability meant the weapons often failed to work. Fighter crews and airmen were disheartened by their lack of success. Commanders remained distant from their men and were disinterested in combat.

Olds took charge of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, the "Wolfpack," at Ubon, Thailand, in late September 1966. After purging the Wing staff of "pencil pushers," he placed himself on the flight schedule as a rookie pilot under officers junior to him, and challenged them to train him. "The challenge was to earn their respect," he said later, "and you do that by flying with them." He gave them credit for their experience while demonstrating that he would provide the leadership they'd lacked.

Olds' idea of what a leader should be had been shaped by his experiences playing football and from his own past commanders, most notably leading ace "Hub" Zemke in WWII. Rather than being remote from his men, Olds became the core for their social unit. Rather than inspiring them to fight for a cause or their political leaders, Olds made them want to fight for each other. And he fought with them: while his predecessor had flown twelve combat missions in ten months, Olds would fly 154 during his one-year tour.

Despite being 44, Olds was as strong and aggressive a pilot in the double-supersonic F-4 Phantom as he had been in the P-38 and P-51 half a lifetime earlier. He demanded that aircrews rise to his standards and praised them when they did. After hours, he joined them in the Officers' Club, which became a venue for discussion and a forum for exchanging ideas. Olds created a command environment where all in the Wing believed they could excel and had the opportunity to do so.

Operation Bolo, three months into Olds' tour, symbolized the change. Many would later give Olds sole credit for the operation's success, but in truth it was a product of the growing warrior spirit throughout the 8th TFW. The idea of imitating a strike package, with air-to-air configured Phantoms replacing bomb-laden F-105s, came from one of the wing's planners. Once the scheme was hatched, Olds arranged approval for the mission from higher command and support from other combat wings. Many of the key details, such as hanging F-105 countermeasures pods on the Phantoms so they would look like "Thuds" to North Vietnamese radar operators, came from his men. And Olds scored just one of the seven MiG kills on the January 2, 1967 mission.

Three further kills in May put him on threshold of being the first US ace in Vietnam. For the rest of his tour, Olds passed up many opportunities for fifth kill, fearing that the Air Force would make him leave his troops and return to the US as a symbolic hero. Not until July 1972 did another USAF pilot pass his score.

The Wolfpack's performance improved from five kills and a 2:1 kill ratio before Olds' arrival to 18 kills and a 4:1 ratio during his tenure, due to no other factor than the charisma of the man in charge. Indeed, the improvement happened even though operating restrictions and political interference remained, the North Vietnamese Air Force grew stronger, and equipment problems got worse. (Anyone who ever heard Olds talk of his Vietnam experiences will never forget the anger he maintained towards the ineffective AIM-4 Falcon, "that god-damned missile!")

It was during his time in Vietnam that Olds' extravagant, waxed and non-regulation handlebar moustache appeared, worn as an act of defiance and individuality. Despite these traits - or because of them - he was universally admired by his peers and subordinates. Few other commanders or MiG killers could make such a claim.

After his tour with the 8th TFW, Olds was promoted to Brigadier General and became commandant of cadets at the US Air Force Academy, imparting his values on future officers. He made a brief return to Vietnam in 1972, on an inspection trip to determine why the USAF was being outscored by the Navy in air-to-air combat. Upset that the Air Force's fighter crews had lost so much of the motivation he'd imparted that they "could not fight their way out of a wet paper bag," he volunteered to return to the war in a combat role. When his request was turned down, he filed his retirement papers.

In retirement, Olds was council member in Steamboat Springs, Colorado and a public speaker. He enthralled audiences with his combat experiences and inspired them with his thoughts on military ethos.

Olds was a true warrior - he lived to prove himself against an opponent, whether on the gridiron or in the air. Unlike other Air Force heroes like Rickenbacker, Doolittle, or Yeager, he was not concerned with developing aviation for the greater good of mankind and did not see warfare as unpleasant or a last resort. He once told a room full of Strategic Air Command officers, "Peace is not my profession!" Aerial combat, not simply flying, was his reason for being. And while time tarnished the reputation of other famous pilots from Vietnam, he remained a hero and inspiration to fellow aviators right up to his death.

Olds was bold and vocal. However, he was always willing to demonstrate that his beliefs were not simply words. And he was approachable, taking the time to talk with almost everyone he met.

He was also a man of his word, as exemplified by the names painted on his aircraft. When his West Point roommate, nicknamed "Scat", was washed out of pilot training, Olds promised to carry Scat's name into battle on his assigned aircraft. And he did so on every single one - from Scat I, a P-38, up to Scat XXVII, his personal F-4C at Da Nang.

words: Mark Munzel

The above article was published in July 2007 in Fence Check Magazine.

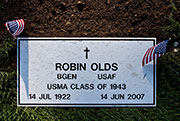

The memorial service on June 30th was overflown by a P-51, two T-33s, and a MiG-17 in addition to a flight of F-16s from the local CO ANG, and the missing man formation was performed by F-4 Phantoms in Vietnam-era markings. Following the service, Olds' remains were interred at the Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs.

Fly Over details:

2 x T-33 - Roy Halliday, CO and William Fowler, SC - both in Thunderbirds scheme.

1 x P-51 "Crusader" - Joe Thibodeau, CO

4 x F-16 - CO ANG KBKF

1 x MiG-17 - Jack Wilhite, CO

4 x F-4 - KHMN

F-4 details:

71237/AF-295/TD shark mouth

72494/AF-308/TD

74626/AF-309/HD shark mouth

74665/AF-251/HD

All F-4s were painted in Vietnam gloss camo which is to become the new standard for the fleet.

F-4 Pilots/Callsigns:

Phantom 1 - Lt Col Anothony "ET" Murphy (TD) (Phantom East 2006)

Phantom 2 - Major Chris "rALF" Vance (TD) (Phantom East)

Phantom 3 - Major John "Shamu" Markle (HD) (Phantom West)

Phantom 4 - Col JD "Bare" Lee (HD)

For the flyovers the aircraft were stacked over The Garden Of The Gods as follows:

T-33s 9500'

P-51 10500'

F-16s 11500'

MiG-17 12500'

F-4s 13500'

All aircraft were called in from the stack by Scenic Control with heading corrections called out as they approached the cemetery - timing was controlled by Senor Controller at the cemetery - there were no TOT as everything was dependent on the timings on the ground.

The T-33s were 30 seconds apart and all other formations were 1 minute spaced and all were flown at 500' AGL.

thanks to:

Major James Wilson, Major John "Huge" Huguley, Casey Hale.